The universe’s funhouse mirrors are revealing a difference between how dark matter behaves in theory and how it appears to act in reality.

Dark matter is the invisible glue that keeps stars bound together inside a galaxy. It makes up most of a galaxy’s mass and creates an invisible scaffold that tethers galaxies to form clusters.

Dark matter does not emit, absorb, or reflect light. It does not interact with any known particles. Its presence is known only through its gravitational pull on visible matter in space.

Although dark matter is lightly smeared throughout the universe, it is heaped in regions of space called galaxy clusters. Each of these massive clusters, held together by gravity, is made up of about 1,000 individual galaxies — each of which carries its own dollop of dark matter.

In a new study in the journal Science, Yale astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan and a team of international researchers analyzed Hubble Space Telescope images from several massive galaxy clusters and found that the smaller dollops of dark matter associated with cluster galaxies were significantly more concentrated than predicted by theorists.

The finding implies there may be a missing ingredient in scientists’ understanding of dark matter.

“There’s a feature of the real universe that we are simply not capturing in our current theoretical models,” said Natarajan, a senior author of the study and a professor of astronomy and physics at Yale. “This could signal a gap in our current understanding of the nature of dark matter and its properties, as this exquisite data has permitted us to probe the detailed distribution of dark matter on the smallest scales.”

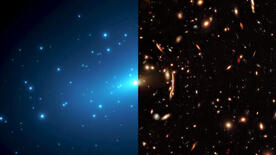

Astronomers are able to “map” the distribution of dark matter within galaxy clusters via the bending of light the galaxies produce — a concept called gravitational lensing. Like a funhouse mirror, gravitational lensing distorts the shapes of background galaxies that appear in telescope images of cluster galaxies. The higher the concentration of dark matter in a cluster, the more dramatic the observed lensing effects.

The researchers used images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, coupled with spectroscopy from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, to produce high-fidelity dark-matter maps.

A 3D view of the data showed the presence of dark matter hills, mounds, and valleys. From this perspective the mapped dark matter looks like a mountain range, with peaked regions. The peaks are the dollops of dark matter associated with individual cluster galaxies.

The especially high quality of the study’s data allowed the researchers to test whether these dark matter landscapes matched theory-based computer simulations of galaxy clusters with similar masses, located at roughly the same distances.

What they discovered was that the simulations did not show any of the same level of dark-matter concentration on the smallest scales — the scales associated with individual cluster galaxies.

“To me personally, detecting a gnawing gap — a factor of 10 discrepancy in this case — between an observation and theoretical prediction is very exciting,” Natarajan said. “A key goal of my research has been testing theoretical models with the improving quality of data to find these gaps. It’s these kinds of gaps and anomalies that have often revealed that either we were missing something in the current theory, or it points the way to a

brand-new model, which will have more explanatory power.”

Natarajan has spent more than a decade confronting theoretical models of dark matter with data from gravitational lensing. “The quality of data and the sophistication of models have only now converged to permit stress testing of the cold dark matter paradigm, and it has revealed a crack,” she said.

Natarajan said the team, which includes researchers from Italy, the Netherlands, and Denmark, plans to continue stress testing theories of the nature of dark matter. The study’s first author is Massimo Meneghetti of the Observatory of Astrophysics and Space Science in Bologna, Italy.